- posted: Aug. 14, 2024

With the main focus of chiropractic being on the spine, many people think chiropractors can only help with problems such as back pain, neck pain, and headaches.

And while it’s true that chiropractors can often help people with pain, there is so much more to chiropractic than just treating pain. Chiropractic care is really about total health and well-being. It’s about helping people to feel great, and get the most out of life, functioning at their optimal potential.

To understand how this works, it’s important to consider the spine’s role in the body. The spine is there to protect the spinal cord, which is part of the central nervous system. The spine is like a set of armor made up of segments, so that it can bend and move naturally with the body.

A spinal segment consists of two vertebrae and the joints that connect them. There is a disc in-between each vertebra that acts as a cushion.

Underneath that armor, a whole lot is happening. Messages travel from around the body, up the spinal cord and into the brain. The brain processes those messages and sends replies back down the spinal cord to tell the body how to respond. The central nervous system is one big information highway, and it carries vital messages to every part of your body.

Sometimes, the wear and tear of everyday life can impact the spine and cause spinal segments to move in a way that is different to normal – in a dysfunctional way.1 That wear and tear can happen gradually, such as from bad posture, or it can happen suddenly, which is common with sports injuries.

Because of the close relationship between the spine and the nervous system, everyday strains can actually impact the flow of information between the brain and the body. Messages may not be delivered to the brain, or they may be inaccurate.2, 3

When that miscommunication occurs due to abnormal movement in the spine, chiropractors call this a ‘vertebral subluxation’.3 A vertebral subluxation occurs when you have abnormal movement in the spine that interferes with the accurate flow of information between your brain and body.3 As a chiropractor our number one job is improve the function of your spine.

By making fast, gentle adjustments to the spine, we can help restore its natural movement and improve the flow of accurate information throughout your nervous system.2, 4-8 A great example of this would be to view your central nervous system like the ‘engine’ of your body and the Chiropractor acts like the mechanic - tuning the spine and central nervous system so that your body can run like a race car.

People often ask about when they are being adjusted, what are the popping sounds that occur with some adjustments. We always like to point out early on in the piece that these popping sounds are completely harmless – they’re just the release of gas from between spinal segments,9 and they are no more significant than any other release of gas from the body.

So let us give you a bit of background information about how your brain and nervous system work.

The interesting thing here is that how you – or your brain – sees a situation may not be entirely accurate. Sometimes your brain even ‘fills in the blanks’ on your behalf!15 So this means that your experience isn’t 100% based on reality, but is instead a perception of reality.

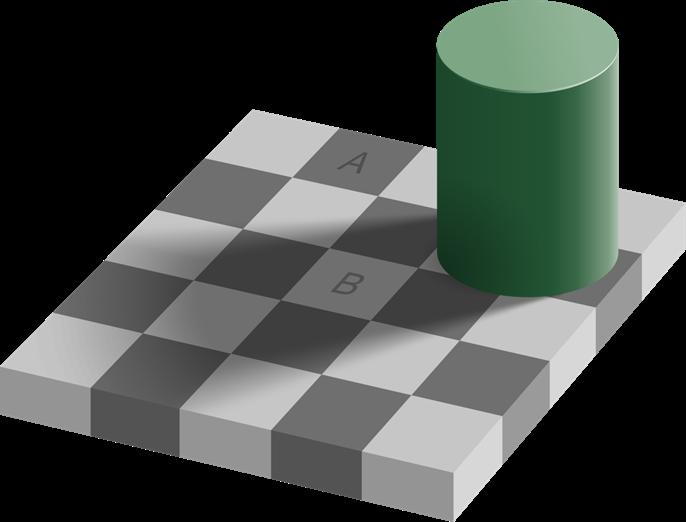

Let’s look at an example of how the brain fills in the blanks. Look at this picture and consider which square is darker, square A or square B?

They’re actually exactly the same color. It is incredible isn’t it! Your brain does not just ‘see’ what the eyes tell it. It interprets what the eyes tell it based on other information it has already stored up.16

In this case you see square A as darker than square B, because square B is in the shadow of the green cylinder, while square A is outside the shadow. Based on your brain’s past experience it will ‘decide’ for you that if a square in a shadow reflects the same amount of light as a square outside the shadow, then it must be a lighter shade of grey.

This ability of the brain to fill in the gaps or create its own perception of reality can become a problem for you if your brain is not accurately perceiving what’s going on inside and outside of your body.17-19 What happens if the brain’s map of the body is inaccurate, or if it is interpreting information based on faulty perceptions? It may mean that your brain responds to environmental cues ineffectively.17-19

But how would you know if your brain’s map of the body or its knowledge of the environment was inaccurate?

You might find that you become a bit clumsy.20 That you stub your toe often, or catch your elbow on door frames. You may find that your golf swing is out. Or that your concentration is just not what it used to be. Or you may find yourself over-reacting emotionally to a situation.

This is where chiropractic comes into the picture because the vertebral subluxations mentioned earlier alter the way your brain processes information coming from the environment.3 So by correcting vertebral subluxations chiropractic care can help restore the function of the brain and the central nervous system, improving the accuracy of your brain’s map of the body, so that you can operate at your best.2, 9 Let's examine this in a little more detail so it makes more sense.

We know that our brain receives information about your body and the environment from your sensory organs – such as our eyes, ears and nose.

But did you know that the muscles in your body are also sensory organs? As your body moves, muscles stretch, and this information is sent to your brain, so that it knows what your body is doing.21

When you think of muscles you probably think of your biceps and triceps. And you won’t necessarily think of the small muscles close to your spine and skull.

These small muscles do in fact play a very important role – they tell your brain what your spine is doing, which represents what the core of your body is doing.21, 22

However, if your spinal segments begin to move in a dysfunctional way – for example due to an injury or bad posture – then that communication between your spinal muscles and your brain becomes distorted, which means you have a communication breakdown between your brain and your body. This is exactly what happens when you have a vertebral subluxation in your spine.3

If you have a vertebral subluxation it may cause background noise for your brain or your brain might not be getting adequate information about what’s happening in your body, and will therefore have to fill in the blanks.2, 3

This is where your chiropractor comes in. A chiropractor will gently adjust any dysfunctional spinal segments, these vertebral subluxations that are continuously mentioned, to restore healthy movement. This can improve the communication between your brain, your body and the environment.3, 23 It is a lot like rebooting a computer.

When your brain can accurately perceive what is going on inside and out, it can control your body better for the situation at hand, and move muscles in the right order. 17-19 This means your body moves accurately, you have fewer accidents, and you can function and perform at your best.

So chiropractic care is all about improving the function of your nervous system so you can function at your optimal potential.

References:

1. Henderson CN. The basis for spinal manipulation: Chiropractic perspective of indications and theory. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. Apr 16 2012.

2. Haavik H, Murphy B. The role of spinal manipulation in addressing disordered sensorimotor integration and altered motor control. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. Apr 5 2012;22(5):768-776.

3. Haavik Taylor H, Holt K, Murphy B. Exploring the neuromodulatory effects of the vertebral subluxation and chiropractic care. Chiropr J Aust. 2010;40(1):37-44.

4. Haavik H, Murphy B. Subclinical neck pain and the effects of cervical manipulation on elbow joint position sense. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. Feb 2011;34(2):88-97.

5. Haavik Taylor H, Murphy B. Altered cortical integration of dual somatosensory input following the cessation of a 20 minute period of repetitive muscle activity. Exp Br Res. 2007;178(4):488-498.

6. Haavik Taylor H, Murphy B. Altered sensorimotor integration with cervical spine manipulation. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2008;31(2):115-126.

7. Haavik Taylor H, Murphy B. Altered central integration of dual somatosensory input after cervical spine manipulation. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(3):178-188.

8. Haavik Taylor H, Murphy B. The effects of spinal manipulation on central integration of dual somatosensory input observed after motor training: a crossover study. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. May 2010;33(4):261-272.

9. Kawchuk GN, Fryer J, Jaremko JL, Zeng H, Rowe L, Thompson R. Real-time visualization of joint cavitation. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0119470.

10. Cooke SF, Bliss TV. Plasticity in the human central nervous system Brain. 2006;129(Pt 7):1659-1673.

11. Mozolic JL, Hugenschmidt CE, Peiffer AM, Laurienti PJ. The Neural Bases of Multisensory Processes. In: Murray MM, Wallace MT, eds. Multisensory Integration and Aging. Boca Raton FL: Llc.; 2012.

12. Buneo CA, Andersen RA. The posterior parietal cortex: sensorimotor interface for the planning and online control of visually guided movements. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44(13):2594-2606.

13. Holmes NP, Spence C. Multisensory integration: space, time and superadditivity. Current Biology. Sep 20 2005;15(18):R762-764.

14. Bassett DS, Yang M, Wymbs NF, Grafton ST. Learning-induced autonomy of sensorimotor systems. Nat Neurosci. May 2015;18(5):744-751.

15. Durgin FH, Tripathy SP, Levi DM. On the filling in of the visual blind spot: some rules of thumb. Perception. 1995;24(7):827-840.

16. Adelson EH. Perceptual organization and the judgment of brightness. Science. Dec 24 1993;262(5142):2042-2044.

17. Abbruzzese G, Berardelli A. Sensorimotor integration in movement disorders. Movement Disorders. 2003;18(3):231-240.

18. Konczak J, Corcos DM, Horak F, et al. Proprioception and motor control in Parkinson's disease. J Mot Behav. Nov 2009;41(6):543-552.

19. Schieppati M, Nardone A, Schmid M. Neck muscle fatigue affects postural control in man. Neuroscience. 2003;121(2):277-285.

20. Sigmundsson H. Disorders of motor development (clumsy child syndrome). J Neural Transm Suppl. 2005(69):51-68.

21. Pickar JG. Neurophysiological effects of spinal manipulation. Spine J. Sep-Oct 2002;2(5):357-371.

22. Goodworth AD, Peterka RJ. Contribution of Sensorimotor Integration to Spinal Stabilization in Humans. J Neurophysiol. July 1, 2009 2009;102(1):496-512.

23. Holt KR. Effectiveness of Chiropractic Care in Improving Sensorimotor Function Associated with Falls Risk in Older People Auckland: General Practice and Primary Healthcare, University of Auckland; 2014.

24. Tsuji T, Matsuyama Y, Goto M, et al. Knee-spine syndrome: correlation between sacral inclination and patellofemoral joint pain. J Orthop Sci. 2002;7(5):519-523.

25. Borggren CL. Pregnancy and chiropractic: a narrative review of the literature. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine. Spring

12/07/received

03/22/revised

03/22/accepted 2007;6(2):70-74.

26. Miller JE, Newell D, Bolton JE. Efficacy of chiropractic manual therapy on infant colic: a pragmatic single-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. Oct 2012;35(8):600-607.

27. Reed WR, Beavers S, Reddy SK, Kern G. Chiropractic management of primary nocturnal enuresis. Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics. 1994;17(9):596-600.

28. Alcantara J, Ohm J, Kunz D. The safety and effectiveness of pediatric chiropractic: a survey of chiropractors and parents in a practice-based research network. Explore (NY). Sep-Oct 2009;5(5):290-295.

29. Todd AJ, Carroll MT, Robinson A, Mitchell EK. Adverse Events Due to Chiropractic and Other Manual Therapies for Infants and Children: A Review of the Literature. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. Oct 30 2014.

30. Doyle MF. Is chiropractic paediatric care safe? A best evidence topic. Clinical Chiropractic. 9// 2011;14(3):97-105.

31. Glazener CM, Evans JH, Cheuk DK. Complementary and miscellaneous interventions for nocturnal enuresis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005(2):CD005230.

32. Robson WLM. Evaluation and Management of Enuresis. N Engl J Med. April 2, 2009 2009;360(14):1429-1436.

33. Carrick FR. Changes in brain function after manipulation of the cervical spine. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. Oct 1997;20(8):529-545.

34. Wingfield BR, Gorman RF. Treatment of severe glaucomatous visual field deficit by chiropractic spinal manipulative therapy: a prospective case study and discussion. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2000;23(6):428-434.

35. Kelly DD, Murphy BA, Backhouse DP. Use of a mental rotation reaction-time paradigm to measure the effects of upper cervical adjustments on cortical processing: a pilot study. Journal of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics. 2000;23(4):246-251.

36. Haavik Taylor H, Murphy B. Cervical spine manipulation alters sensorimotor integration: A somatosensory evoked potential study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118(2):391-402.

37. Mieritz RM, Hartvigsen J, Boyle E, Jakobsen MD, Aagaard P, Bronfort G. Lumbar motion changes in chronic low back pain patients: a secondary analysis of data from a randomized clinical trial. Spine J. Nov 1 2014;14(11):2618-2627.

38. Branney J, Breen AC. Does inter-vertebral range of motion increase after spinal manipulation? A prospective cohort study. Chiropr Man Therap. 2014;22:24.

39. Niazi IK, Turker KS, Flavel S, Kinget M, Duehr J, Haavik H. Changes in H-reflex and V-waves following spinal manipulation. Exp Brain Res. Jan 13 2015.

40. Hillermann B, Gomes AN, Korporaal C, Jackson D. A pilot study comparing the effects of spinal manipulative therapy with those of extra-spinal manipulative therapy on quadriceps muscle strength. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. Feb 2006;29(2):145-149.

Locations

3448 Forestbrook Road

Myrtle Beach, SC 29588, USA

Office Hours

CALL or TEXT for an appointment (843) 236-9810

Dr. Tori Ritchie, DC and Dr. Sandra Buffkin, DC

9:00 am - 1:00 pm

1:00 pm - 6:00 pm

9:00 am - 4:00 pm

9:00 am - 6:00 pm

9:00 am - 1:00 pm

Closed

Closed